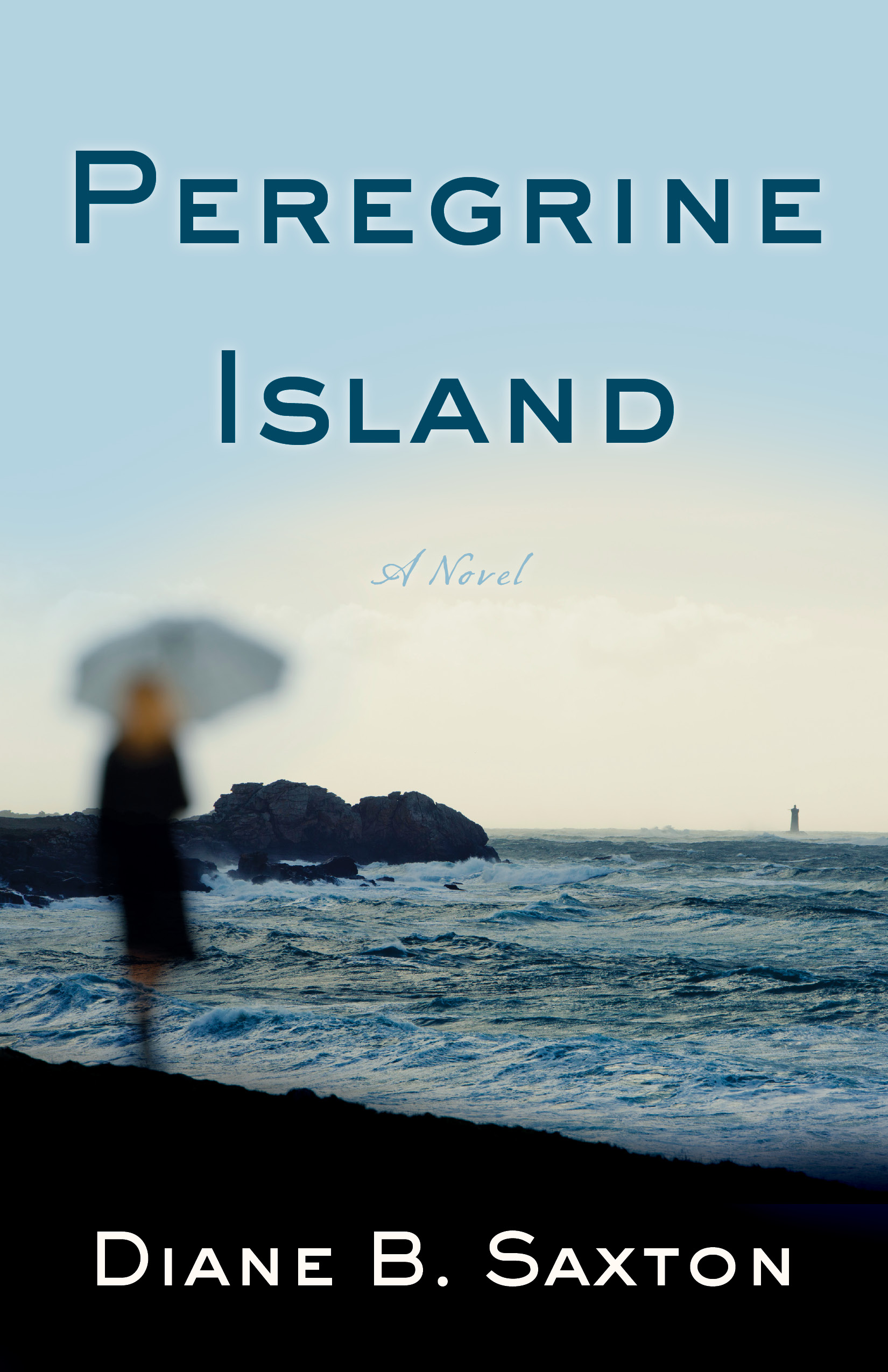

Winter, owner of Peregrine Island, steps inside the painting she inherited from her father.

…and I pulled my attention back to my painting, the one the museum experts were coming to see, where it hangs in the middle of the faded cherry-paneled wall.

A misty, dreamy scene by the ocean, the Long Island Sound, near here, I supposed, on a quay off an old, cobbled road, rough waves slapping at the stone wall. People I have stared at all my life: A woman in a fitted, ankle-length skirt holds the hand of a child. A few feet away, a man in a fedora bends over the railing and gazes into the water. People who seem to belong more to my past than my own. Early evening interpreted by shades of gray and a lit brass lamppost with an ornate overhang. Even so, the colors of the half-light remain remarkably pure, for every line, every shade and curve, is delineated. Every stone, every wave—you can see that it is high tide—each grain of sand, each section of seaweed, the mother’s slight smile, the gloved hand of the man with the hat. Clear and haunting in the pale, diffuse light.

I looked out the window. It could be this evening but for their dress and the time of year. The figures are familiar to one another—even the suited gentleman in the near distance whose hand is raised in greeting, a small, curly-haired dog at his heels. I feel as if I know them all, and well. The smell of the Sound: a reek of fish mixed with brine; the damp coolness in the air; the wind that blows my hair and scrubs my cheeks. I put my hands up to my own cheeks and held them there for a moment, mesmerized by the probing black eyes of the young woman in the painting. . . .