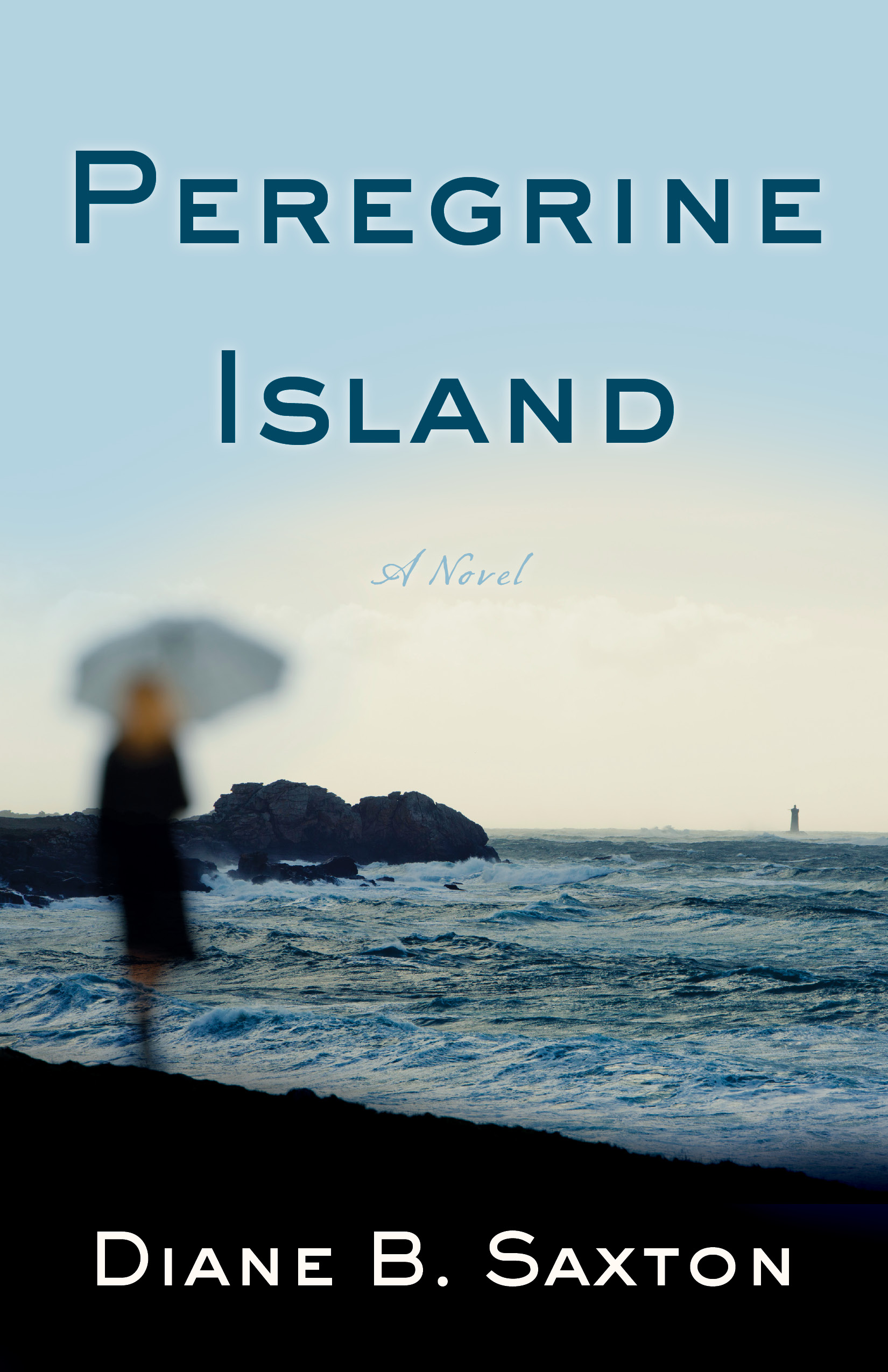

PEREGRINE ISLAND

People who live on the shores of an ocean or a sea know what to do when a squall comes in. Lovers of salt-whippy air and fermenting waves enjoy the kick they get from the sudden, short- lived storm.

But not Winter Peregrine, sole owner of a small island, and mother and grandmother of a family insulated by the waters of the Long Island Sound. Never has she waded out to a waiting skull, rowed till she collapsed, nor has she experienced the thrill of hooking a bluefish, a flounder, or a sea bass. Nothing she does allows the sport of the sea into her life. She prefers to observe it—and from her shut-tight windows, she has learned its secrets well. Nevertheless, in a squall, Winter would probably perish.

Unlike her daughter, Elsepath, who relishes risk. Hooking a fish is child’s play for Elsie, as she prefers to be called. She enjoys a fight for survival. Water-skiing upside down on her fingertips while ricocheting between rocks at low tide—this is another one of her passions. And squalls—one would assume Elsie thrives on them.

Her daughter, tiny Peda, however, would never hook a fish, never water-ski where crabs multiply and make their homes. To become one with her habitat and to safeguard sea life from sudden ravages—this, she sees as her mission. Particularly in a squall.

In our mind’s eye, we picture the family on the beach: the grandmother on wet sand, her forehead coated with the sweat of icy fear; way ahead of her, the daughter, looking back, knee- deep in a stony tidal pool. And behind them both, we imagine we hear humming, and the skip and splash of a little girl’s feet. The three of them together are like inharmonious survivors on a raft, fated to capsize if thrust together too long, we think. But then again . . . maybe not. For what you see, or think you see, on Peregrine Island is seldom what it seems.